MapReduce: Simplified Data Processing on Large Clusters

Published December 2004

Abstract

MapReduce offers an abstraction for large-scale computation by managing the scheduling, distribution, parallelism, partitioning, communication, and reliability in the same way to applications adhering to a template for execution.

Introduction

Programming Model

MR offers the application-level programmer two operations through which to express their large-scale computation.

Note: the types I offer here are not identical to the original map reduce; my version is simplified somewhat. Though both are equivalent in the sense that they reduce to one another.

type Map T K V = T -> [(K, V)]type Reduce K V U = K -> [V] -> U

Run-time type requirements (necessary for the implementation) are that K is both “shuffle-able” and equality-checkable. The ability to shuffle a type depends on one’s partitioning function. In the paper, this may be a requirement on orderability or hashability.

Evaluation’s signature, as presented in the MR paper, in pseudo Haskell, would be:

-- Assume all are Serializable

evaluate :: (Hashable k, Eq k) => Map t k v -> Reduce k v u -> [t] -> [u]

Example

Word count can be implemented pretty easily with the above definitions, where we map over a list of words, converting each word into the pair (word, 1), then the reduce operations sums the second part of each pair.

More Examples

Other uses of map reduce include substring search, graph reversal (indexing), bag-of-words computation for language processing, and distributed sort (under specific shuffling functions).

Implementation

Map reduce was built with the intent of distributing work among commodity hardware with up to thousands of nodes. Storage is assumed to be HDD and inexpensive. Network assumptions are that we have 100 Mbps to 1 Gbps.

Execution Overview

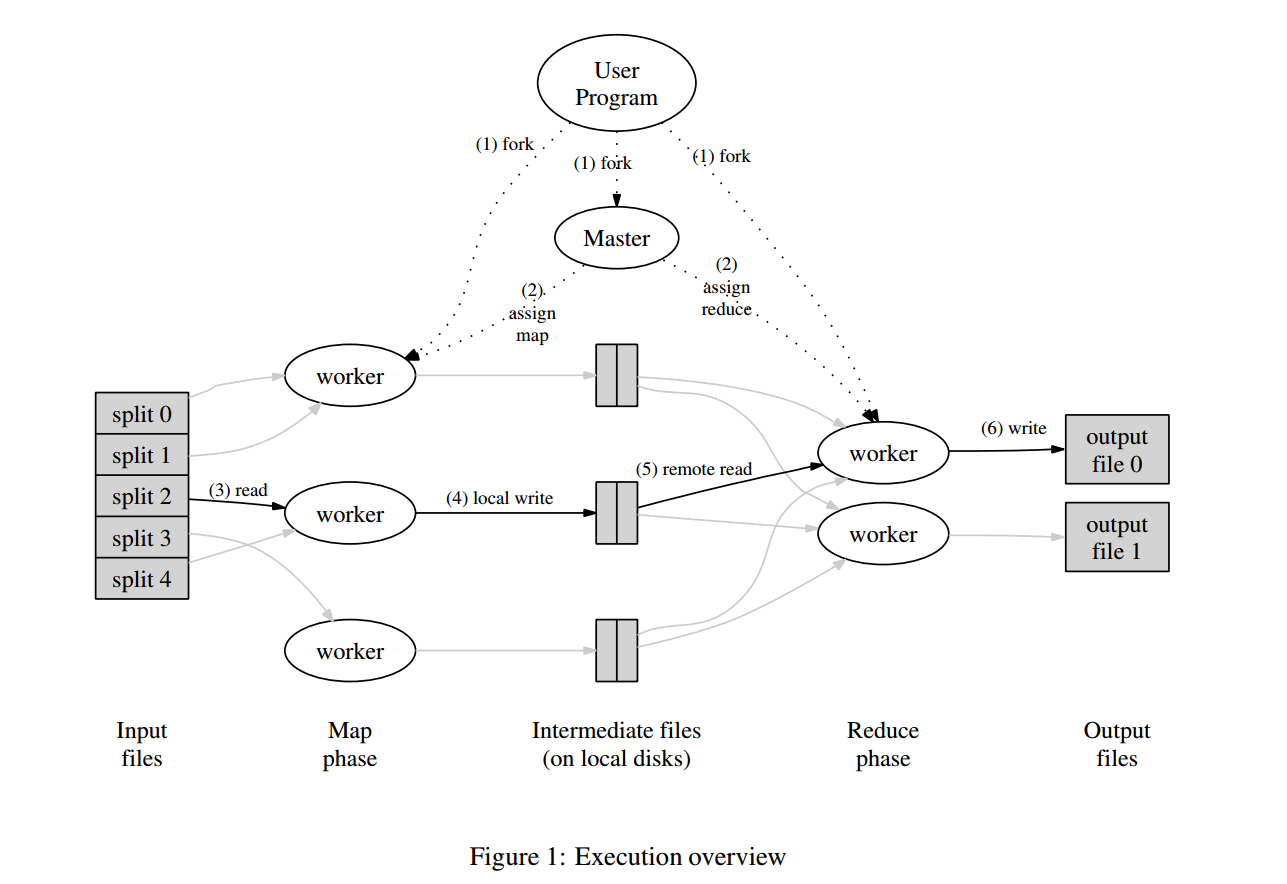

For \(M\) map tasks and \(R\) reduce tasks, with a partitioning function (which may be either a hash or interval rank, depending on whether output was expected to be sorted or not), MR works in the following manner.

- The input is split into \(M\) pieces and made available for distributed reading.

- A master node initializes the state for the map tasks and reduce tasks; scheduling them with dependencies.

- Map workers apply the map function to their chunk of the input, which was first copied to local disk. The outputted key/value pairs are buffered in memory and periodically flushed to the local disk.

- After evaluation of the entire map file, the worker notifies the master of the location of its local intermediate output. The master forwards this information to the respective reducer (each mapper creates intermediate output for each reducer).

- A started reduce worker, when notified of the mapper’s location, starts reading the outputted key/value pairs that it is responsible for using an RPC.

- After reading in all of the inputted data from all its map tasks, it performs a sort, possibly out-of-memory if necessary (not a hash-based local shuffle). Then it evaluates each key with the reduce function.

- The reduce worker uploads the result to a distributed store (GFS), then performs an atomic rename upon completion, notifying the master.

The output is then stored in \(R\) separate files, one for each reducer.

From step (4), we see that the total metadata maintained on the master is \(O(MR)\). Scheduling decisions require an additional \(O(M+R)\) amount of work.

Failures are handled simply by re-launching the task when a worker fails to respond to a heartbeat after a certain amount of time. Deduplication is performed on the master (i.e., if a worker is assumed lost, and the task is restarted, but it then sends its results). Thus, only-once reducer input idempotency is maintained by having synchronous evaluation: the master isn’t notified of the map output until it’s completely ready.

Master Failure

The master node is a single point of failure. It can be made reliable, but is so rare that it is often easier to just restart the task.

Failure semantics

Deterministic functions will be equivalent to a sequential run of the program.

Non-deterministic functions result in outputted reduce tasks from some combination of some runs of the program, so they are not guaranteed to be equal to any single run of the sequential program.

Locality

The network-scarcity assumption means that the optimal blocking size for the computation should be around the size that the distributed state store uses, to avoid extra low-capacity blocks from being passed around. For GFS, this was 64MB. By integrating with GFS, the master is able to schedule map tasks in locations that house the actual data. This allows for step (1) from above to avoid any network reads.

Task Granularity

Backup Tasks

Stragglers, caused by bugs or hardware failures, are common with an increase of the number of workers. They are resolved by launching backup tasks near completion, which reduce the probability of all tasks straggling (only one needs to finish). Removing this optimization in the sorting example causes a 44% slowdown.

Refinements

Combiner Function

A combiner function is an associative, commutative Reduce-type function that can be iteratively applied in a tree structure increase the reduce task’s span (level of parallelism). MR applies the combiner on the map task side, which can reduce communication size and overall compute time.

Performance

Performance was tested on 1800 machines with a two-level tree-shaped switched network of 100 Gbps aggregate bandwidth, 2GHz processors, and 3 GBs of RAM per node.

Distributed grep used \(M=15000, R=1\), oversubscribing the map tasks for appropriate task granularity (input was 1TB). End-to-end is 150 seconds.

Terasort takes 891 seconds. For comparison, at the time, the best TeraSort was 1057 seconds. Note that for general sorting, MR recommends a sampling pre-pass for split computations.

MR was observed to be biased towards faster shuffle and input rates. Output is slower because it makes replicated writes.

Experience

Related Work

Conclusions

MR introduced the notion of a restricted, simple API that allows for expressiveness required for many tasks while maintaining simple semantics and enabling distributed processing. Network bandwidth is observed to be the bottleneck. Finally, replication-based variance reduction for latency is introduced as a technique (though it may be used for other goals as well).

Notes

Observations

- MR set the standard assumption that network is constraining; this notion was key in design of such distributed processing systems until newer technologies like Spark emerged, which moved bottlenecks elsewhere (see this performance analysis for more details).

- Output is made reliable by storage to a replicated distributed state store (such as GFS). This interactivity between the execution engine (MR) and the store (GFS) is repeated in open-source versions of the product, such as Hadoop, with its MapReduce and HDFS.

- MR chooses to have a master-in-the loop synchronous evaluation style, where the map task completion alerts the master and then starts the reduce operation. This thinking helps correctness. It was used in subsequent execution engines (like Spark). Unfortunately, even though for one task the \(O(M R)\) state in the master is manageable, especially with an efficient implementation, as the number of concurrent MR tasks increases (as is common nowadays with a shared cluster environment), scheduling becomes a large portion of the overhead that is also unparallelizable.

Weaknesses

- For correctness, MR requires that functions with side effects respect parallel re-entrancy and thread-safety across machines (as well as locally, if multiple tasks can be scheduled on one thread). Typical operations that would violate this are non-idempotent or non-associative or non-commutative transactions to a database.

- As mentioned above, master-in-the-loop evaluation causes scheduling delays. Workers maintaining some metadata themselves could allow for faster transitions between mapping and reducing. With additional bookkeeping (for handling failures), even asynchronous information-passing can be introduced.

Strengths

- Speeding up tail performance through replication is an innovation pioneered by MR (see Backup Tasks).

- MR also was very innovative in usability, considering that it was an early execution engine. Besides the interface itself, MR provided mechanisms for automatically detecting deterministic user-code bugs (via bad record tracking and ignoring), a local execution mode, out-of-band counters, and HTTP-based status information.

- For its time, MR was massively enabling for large-scale computation.

Open Questions

- What would it take to have a master-out-of-the-loop asynchronous execution engine?

- What needs to happen to alleviate the parallel (1) re-entrancy and (2) thread-safety requirements that MR places on its user code in case of failure?