FAISS, Part 1

FAISS is a powerful GPU-accelerated library for similarity search. It’s available under MIT on GitHub. Even though the paper came out in 2017, and, under some interpretations, the library lost its SOTA title, when it comes to a practical concerns:

- the library is actively maintained and cleanly written.

- it’s still extremely competitive by any metric, enough so that the bottleneck for your application won’t likely be in FAISS anyway.

- if you bug me enough, I may fix my one-line EC2 spin-up script that sets up FAISS deps here.

This post will review context and motivation for the paper. Again, the approximate similarity search space may have progressed to different kinds of techniques, but FAISS’s techniques are powerful, simple, and inspirational in their own right.

Motivation

At a high level, similarity search helps us find similar high dimensional real vectors from a fixed “database” of vectors to a given query vector, without resorting to checking each one. In database terms, we’re making an index of high-dimensional real vectors.

Who Cares

Spam Detection

Tinder bot 1 bio: “Hey, I’m just down for whatever you know? Let’s have some fun.”

Tinder bot 2 bio: “Heyyy, I’m just down for whatevvver you know? Let’s have some fun.”

Tinder bot 3 bio: “Heyyy, I’m just down for whatevvver you know!!? I just wanna find someone who wants to have some fun.”

You’re Tinder and you know spammers make different accounts, and they randomly tweak the bios of their bots, so you have to check similarity across all your comments. How?

Recommendations

You’re  or

or  and users clicking on ads keep the juices flowing.

and users clicking on ads keep the juices flowing.

Or you’re  and part of trapping people with convenience is telling them what they want before they want it. Or you’re

and part of trapping people with convenience is telling them what they want before they want it. Or you’re  and you’re trying to keep people inside on a Friday night with another Office binge.

and you’re trying to keep people inside on a Friday night with another Office binge.

Luckily for those companies, their greatest minds have turned those problems into summarizing me as faux-hipster half-effort yuppie as encoded in a dense 512-dimensional vector, which must be matched via inner product with another 512-dimensional vector for Outdoor Voices’ new marketing “workout chic” campaign.

Problem Setup

You have a set of database vectors \(\{\textbf{y}_i\}_{i=0}^\ell\), each in \(\mathbb{R}^d\). You can do some prep work to create an index. Then at runtime I ask for the \(k\) closest vectors, which might be measured in \(L^2\) distance, or the vectors with the largest inner product.

Formally, we want the set \(L=\text{$k$-argmin}_i\norm{\textbf{x}-\textbf{y}_i}\) given \(\textbf{x}\).

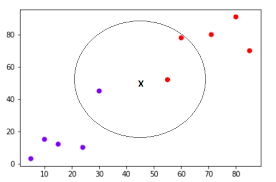

Overlooking the fact that this is probably an image of \(k\)-nearest neighbors, this summarizes the situation, in two dimensions:

Why is this hard?

Suppose we have 1M embeddings at a dimensionality of about 1K. This is a very conservative estimate; but that amounts to scanning over 1GB of data per query if doing it naively.

Let’s continue to be extremely conservative, say our service is replicated so much that we have one machine per live query per second, which is still a lot of machines. Scanning over 1GB of data serially on one 10Gb RAM bandwidth node isn’t something you can do at interactive speeds, clocking in at 1 second response time for just this extremely crude simplification.

Exact methods for answering the above problem (Branch-and-Bound, LEMP, FEXIPRO) limit search space. Most recent SOTA for exact is still 1-2 orders below approximate methods. For prev use cases, we don’t care about exact (though there certainly are cases where it does matter).

Related Work

Before FAISS

FAISS itself is built on product quantization work from its authors, but for context there were a couple of interesting approximate nearest-neighbor search problems around.

Tangentially related is the lineage of hashing-based approaches Bachrach et al 2014 (Xbox), Shrivastava and Li 2014 (L2ALSH), Neyshabur and Srebro 2015 (Simple-ALSH) for solving inner product similarity search. The last paper in particular has a unifying perspective between inner product similarity search and \(L^2\) nearest neighbors (namely a reduction from the former to the latter).

However, for the most part, it wasn’t locally-sensitive hashing, but rather clustering and hierarchical index construction that was the main approach to this problem before. One of the nice things about the FAISS paper in my view is that it is a disciplined epitome of these approaches that’s effectively implemented.

After FAISS

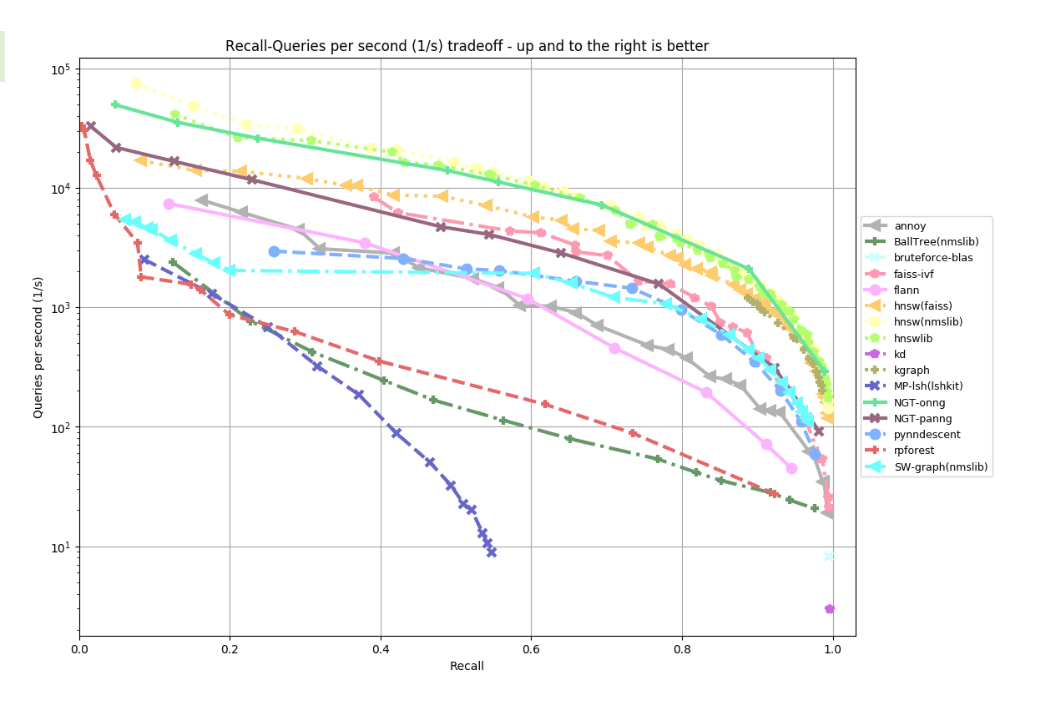

Recently hot new graph-based approaches have been killing it in the benchmarks. It makes you think FAISS is out, HNSW and NGT are in.

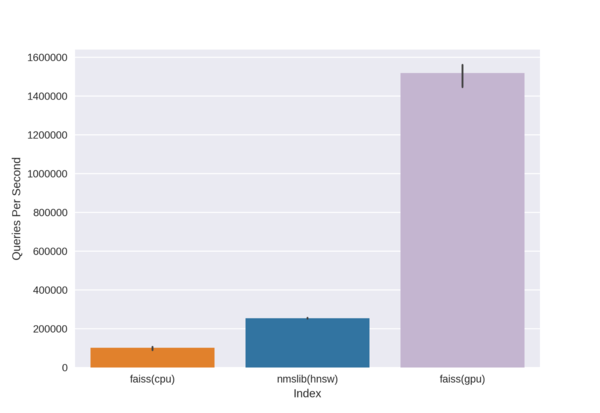

Just kidding. Like the second place winners for ILSVRC 2012 will tell you, simple and fast beats smart and slow. As this guy proved, a CPU implementation from 2 years in the future still won’t compete with a simpler GPU implementation from the past.

You might say this is an unfair comparison, but life (resource allocation) doesn’t need to be fair either.

Evaluation

FAISS provides an engine which approximately answers the query \(L=\text{$k$-argmin}_i\norm{\textbf{x}-\textbf{y}_i}\) with the response \(S\).

The metrics for evaluation here are:

- Index build time, in seconds. For a set of \(\ell\) database vectors, how long does it take to construct the index?

- Search time, in seconds, which is the average time it takes to respond to a query.

- R@k, or recall-at-\(k\). Here the response \(S\) may be slightly larger than \(k\), but we look at the closest \(k\) items in \(S\) with an exact search, yielding \(S_k\). This value is then \(\card{S_k\cap L}/k\), where \(k=\card{L}\).

FAISS details

In the next post, I’ll take a look at how FAISS addresses this problem.