Ligra: A Lightweight Graph Processing Framework for Shared Memory

Published February 2013

Abstract

Ligra graph processing goals:

- Single machine, shared memory, multicore

- Lightweight

- BFS

- Mapping over vertex subsets

- Mapping over edge subsets

- Adapt to varying vertex degrees

Introduction

Motivation for Single Machine Framework

Lower communication cost allows for performance benefits.

Current demands do not necessitate the distributed computation framework previous implementations provide:

- Largest non-synthetic dataset has <7B edges

- All papers except Pregel use <20B edge datasets, Pregel uses <130B.

High-end hardware reaches 64 cores and 2TB of data. With near-linear speedup that Ligra offers, this doesn’t suffer from issues that distributed systems do.

Capabilities

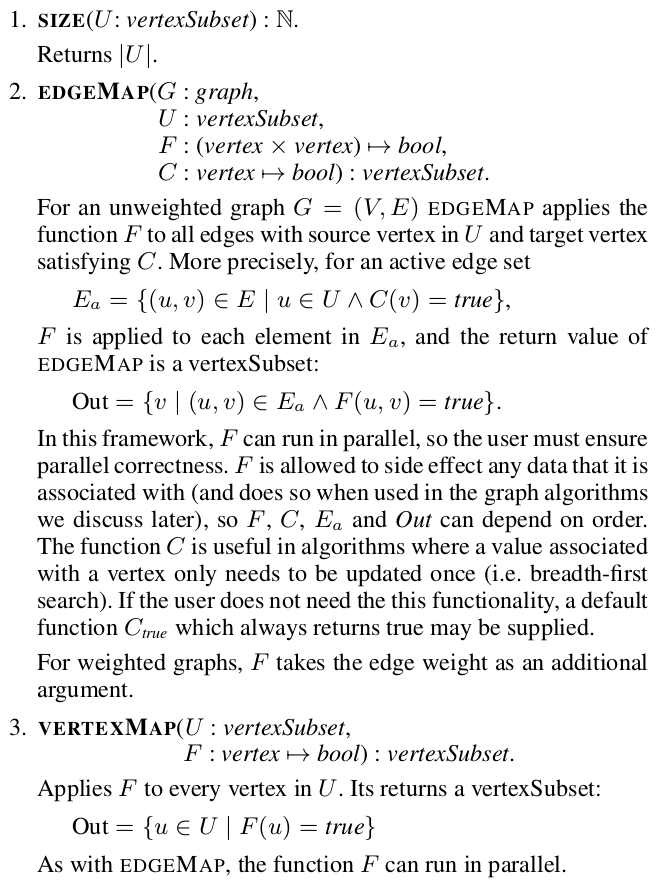

Ligra offers a few primitives to operate on graphs.

Data Types

A graph \(G = (V, E)\) is represented internally in Ligra by what is effectively an adjacency list, but users do not interact with it.

A \(vertexSubset\), \(S\subset V\), is the fundamental datatype of in Ligra. Edge information is exposed through operations on subsets, which are identified by the function answering \(v \in S\) for vertices \(v\).

Operations

See the Framework Interface section below.

Proof of Concept

Using the above primitives, Ligra authors implemented:

- BFS

- Betweenness centrality

- Graph radii estimation

- Graph connectivity

- PageRank

- Bellman-Ford single-source shortest paths.

Related Work

Why does Pregel-like computation suck?

- With the recent exception of GraphLab, there is no way to loop over each vertex’s out edges in parallel for processing, which is a problem for high-degree vertices.

- Need to process every vertex, even with no-ops.

What are the limitations of GraphLab, then? Single-graph computation only: no multiple vertex subsets (bidirectional search, forward-backward search disabled).

Preliminaries

Framework

Interface

It’s the derivation of the \(vertexSubset\)s that determines the linearization points for the algorithm’s computation: the sets are a method of control flow as much as they hold data, much like lists in Haskell.

Implementation

Vertex Subset Representation

Sparse representation is an unordered list of vertex indices.

Dense representation is a boolean array of size \(\left|V\right|\).

Vertex mapping has the straightforward parallel implementation.

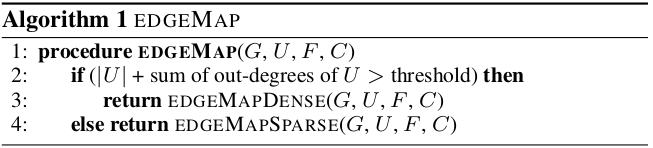

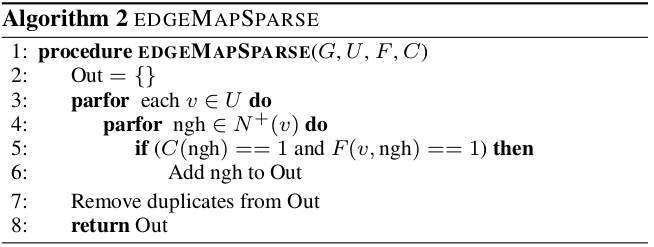

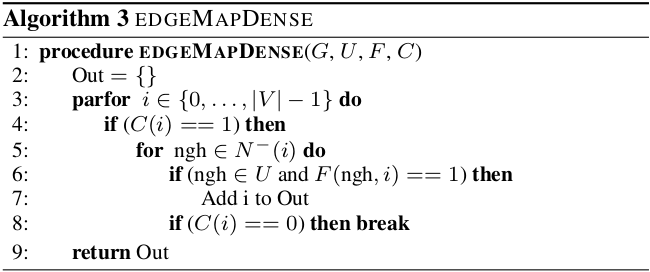

Edge Map

Note that dense conversion is eager in the sense that the threshold is only exceeded in the worst case - if \(F\) always selects each vertex.

Threshold of \( \lvert E\rvert/ \kappa \) used. By looking at Amdahl’s law we can find the optimal time to spend on linear pre/post-processing, but then this is dependent on \(F\)’s runtime and how selective \(C\) is.

Note a \(\kappa\)-threshold implies we can’t speed up more than \(\sim \kappa r\), with \(r\) being the ratio of linear pre/post-processing work time to average \(F\) runtime.

Always produces sparse output (input can be anything). Note that in sparse computations Ligra does not sacrifice parallelism by parallelizing over out-edges as well.

Out-degree sum is a parallelizable, fast operation.

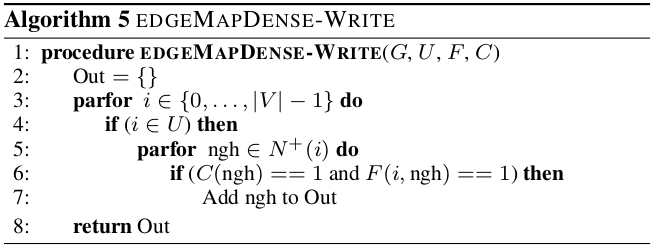

Always produces dense output. Again, can be sparse input. On dense edge mappings, we’re saturating all cores, so there’s no need for nested parallelism.

This is the out-degree version of algorithm 3. Paper says it’s up to the user to figure out which one we should use. It’s kind of silly that they offer both without justifying the tradeoff numerically. Giving both out means you need to maintain the reverse edge mapping (which they do, check the code). The tradeoff is as follows: the in-degree version (Algorithm 3) lets you break the loop if the condition function \(C\) tells you to; this reduces total work. However, each such loop can’t be parallelized, which is a problem for skewed vertex indegree cases, and it’s also the only reason for keeping the extra edges around.

Graph Representation

Edges stored in a one-dimensional array. Vertices own partitions of this array, so a vertex array delimits vertex partitions. Thus, edge array only needs to store the target vertex and vertex array only needs to store one endpoint. Very efficient memory of \(i(\lvert V\rvert + \lvert E\rvert)\) where we use \(i\) bytes per index.

To add an edge, we’d need to insert in the middle of an array. Thus, Ligra only works with static graphs.

Optimizations

Described in line with the implementations.

Applications

Experiments

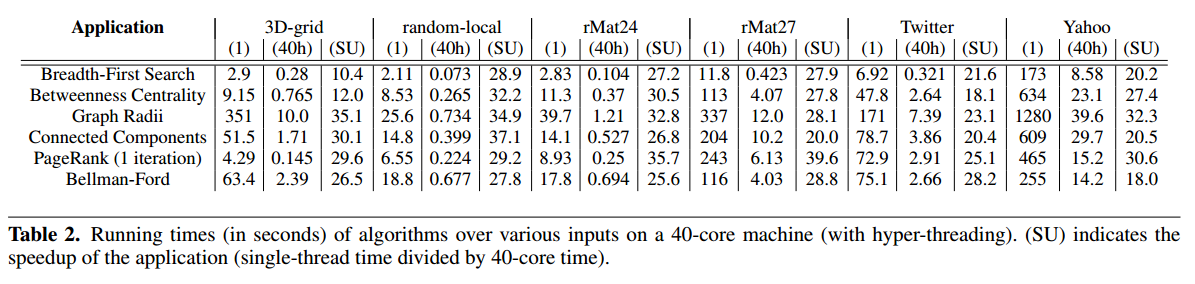

See the paper for details of the graphs and algorithms.

Ligra scales extremely well - the fact that it gets linear speedups into hyperthreads means that it’s very cache-effective. It also means there’s room to grow, speed-wise, as CPU parallelism increases.

Scalability is one thing, though, if distributed systems can run more machines, albeit for more money, but get the job done sooner, who cares? Time is more valuable. The thing is, they don’t. For example, their 40-core quarter-TB finished Bellman-Ford single-source shortest paths in 2 seconds for a \(2^{27}\)-vertex binary tree compared to 20 seconds for a 300-node commodity Pregel cluster for a tree half as large.

Conclusion

Certain algorithms require graph modifications. Ligra needs a memory-efficient adjacency list implementation (to handle large graphs so it is comparable to other frameworks).

GPU future work is posited.

Notes

Observations

- Does no order over out-edge calling prevent certain algos? Doesn’t look like it.

- The framework doesn’t operationalize reduction for you. This means \(F\) needs to take care of it in a manner that maintains parallel correctness. This is OK with atomic add operations, for instance, as page rank does, but not for more complex ops. However, it seems like the reduce step is fairly small. Even with multi-word reduce results, one can use CAS with optimistic synchronization (as the Betweenness Centrality operation does), probably to good effect.

- By enabling the user to maintain active vertex subsets, we don’t need to do expensive no-ops on the entire graph like the distributed frameworks do as they near convergence in iterative computations.

Weaknesses

- During-computation graph modification is important: in connected components, we can perform path shortening in a manner similar to union-find. This speeds up convergence (since new cluster labels propagate faster), but requires the ability to add edges.

- We have to perform a new vertex-sized buffer allocation (and clear it) on every edge map. This is unavoidable if we want to track multiple sets at once, but adds significant linearization cost to the algorithm: new buffer allocation code. Buffers are not bitsets, but boolean arrays, for atomic updating.

- Sparse sets should be pre-sorted if we’re making an \(\mathsf{edgeMapDense}\) call - otherwise we’re making on average a linear membership check \(\text{ngh}\in U\) on every thread for every parallel operation. Sparse to dense conversions shouldn’t happen too often, but it’s still an issue.

Strengths

- Ligra correctly observed the need for reducing communication and control-plane overhead of bulk synchronous parallel systems for graph computations. It also rightly observed that we can satisfy these requirements by using a PRAM model, with a flexible working set that lets us fully saturate machine parallel compute. This is important because graph computations will not be statically embarrassingly parallel, and Ligra adapts to the graph.

- The above adaptation lead to incredible scalability, whooping the other frameworks in speed, with cheaper performance, too.

Takeaways

- Do similar atomics exist for GPUs? Would GPUs have the memory size, memory bandwidth, and coherency/sharing capability that Ligra fully utilizes? Probably not. But extremely high numbers of CPU cores per machine are foreseeable for increasing parallelization.

- Will we be able to keep using PRAM for graph processing? This was published in 2013. Do those TB assumptions still hold now? In terms of existing data sets, the answer is still yes - most datasets people work with are well under the 2TB cutoff. However, this may be due to simply what people can handle, not what they want to. Certainly with ad-tech and web related data graphs can easily scale above 10TB range. However, on a practical level, RAM will be able to keep up with a lot of use cases.

Open Questions

- Can some frameworks like Spark take advantage of such notions of dynamic vertex sets? What about the shared memory architecture is essential to Ligra? What prevents a smart distributed system from taking the vertex subset model? Variable vertex sets are feasible.

- Mutable vertex state not feasible currently in Spark

- Control-plane overhead for parallelizing computation during “sparse” stages of computation is still present.

- Can we apply the framework in some hybrid approach - Ligra-like locally, then join info?

- Does there exist an analogue to \(\mathsf{edgeMapDense}\) that is outdegree-based? If we can re-write algorithms to short circuit based on sending nodes’ state, then we can use an out-edge only representation, cutting memory in half (we would still want to provide an option with vertex-neighbor-level parallelism, \(\mathsf{edgeMapDenseWrite}\) would remain.