Subgaussian Concentration

This is a quick write-up of a brief conversation I had with Nilesh Tripuraneni and Aditya Guntuboyina a while ago that I thought others might find interesting.

This post focuses on the interplay between two types of concentration inequalities. Concentration inequalities usually describe some random quantity \(X\) as a constant \(c\) which it’s frequently near (henceforth, \(c\) will be our stand-in for some constant which possibly changes equation-to-equation). Basically, we can quantify how infrequent divergence \(t\) of \(X\) from \(c\) is with some rate \(r(t)\) which vanishes as \(t\rightarrow\infty\).

\[ \P\pa{\abs{X-c}>t}\le r(t)\,. \]

In fact, going forward, if \(r(t)=c’\exp(-c’’ O(g(t)))\), we’ll say \(X\) concentrates about \(c\) in rate \(g(t)\).

Subgaussian (sg) random variables (rvs) with parameter \(\sigma^2\) exhibit a strong form of this. They have zero mean and concentrate in rate \(-t^2/\sigma^2\). Equivalently, we may write \(X\in\sg(\sigma^2)\). Subgaussian rvs decay quickly because of a characteristic about their moments. In particular, \(X\) is subgaussian if for all \(\lambda\), the following holds: \[ \E\exp\pa{\lambda X}\le \exp\pa{\frac{1}{2}\lambda^2\sigma^2}\,. \]

On the other hand, suppose we have \(n\) independent (indep) bounded (bdd) rvs \(X=\ca{X_i}_{i=1}^n\) and a function \(f\) that’s convex (cvx) in each one. Note being cvx in each variable isn’t so bad, for instance the low-rank matrix completion loss \(\norm{A-UV^\top}^2\) does this in \(U, V\). Then by BLM Thm. 6.10 (p. 180), \(f(X)\) concentrates about its mean quadratically.

This is pretty damn spiffy. You get a function that’s nothing but a little montonic in averages, and depends on a bunch of different knobs. Said knobs spin independently, and somehow this function behaves basically constant. This one isn’t a deep property of some distribution, like sg rvs, but rather a deep property of smooth functions on product measures.

A Little Motivation

Concentration lies at the heart of machine learning. For instance, take the well-known probably approximately correct (PAC) learning framework–it’s old, yes, and has been superseded by more generic techniques, but it still applies to simple classifiers we know and love. At its core, it seems to be making something analogous to a counting argument:

- The set of all possible classifiers is small by assumption.

- Since there aren’t many classifiers overall, there can’t be many crappy classifiers.

- Crappy classifiers have a tendency of fucking up on random samples of data (like our training set).

- Therefore any solution we find that nails our training set is likely not crap (i.e., probably approximately correct).

However, this argument can be viewed from a different lens, one which exposes machinery that underlies much more expressive theories about learning like M-estimation or empirical process analysis.

- The generalization error of our well-trained classifier is no more than twice the worst generalization gap (difference between training and test errors) in our hypothesis class (symmetrization).

- For large sample sizes, this gap vanishes because training errors concentrate around the test errors (concentration).

For this reason, being able to identify when a random variable (such as a classifier’s generalization gap, before we see its training dataset) concentrates is useful.

OK, Get to the Point

Now that we’ve established why concentration is interesting, I’d like to present the conversation points. Namely, we have a general phenomenon, the concentration of measure.

Recall the concentration of measure from above, that for a convex, Lipschitz function \(f\) is basically constant, but requiring bounded variables. However, these are some onerous conditions.

To some degree, these conditions to be weakened. For starters, convexity need only be quasi-convexity. The Wikipedia article is a bit nebulous, but the previously linked Talagrand’s Inequality can be used to weaken this requirement (BLM Thm. 7.12, p. 230).

Still:

- One can imagine that a function that’s not necessarily globally Lipschitz, but instead just coordinate-wise Lipschitz, we can still give some guarantees.

- Why do we need bounded random variables? Perhaps variables that are effectively bounded most of the time are good enough.

Our goal here will be to see if there are smooth ways of relaxing the conditions above and framing the concentration rates \(r(t)\) in terms of these relaxations.

Coordinate Sensitivity and Bounded Differences

The concentration of measure bounds above rely on a global Lipschitz property: no matter which way you go, the function \(f\) must lie in a slope-bounded double cone, which can be centered at any of its points; this can be summarized by the property that our \(f:\R^n\rightarrow\R\) satisfies \(\abs{f(\vx)-f(\vy)}\le L\norm{\vx-\vy}\) for all \(\vx,\vy\)

Moreover, why does it matter that the preimage metric space of our \(f\) need to, effectively, be bounded? All that really matters is how the function \(f\) responds to changes in inputs, right?

Here’s where McDiarmid’s Inequality comes in, which says that so long as we satisfy the bounded difference property, where \[ \sup_{\vx, \vx^{(i)}}\abs{f(\vx)-f(\vx^{(i)})}\le c_i\,, \] holding wherever \(\vx, \vx^{(i)}\) only differ in position \(i\), then we concentrate with rate \(t^2/\sum_ic_i^2\). The proof basically works by computing the distance of \(f(X)\), our random observation, from \(\E f(X)\), the mean, through a series of successive approximations done by changing each coordinate, one at a time. Adding up these approximations happens to give us a martingale, and it turns out these bounded differences have a concentration (Hoeffding’s) of their own.

Notice how the rate worsens individually according to the constants \(c_i\) in each dimension.

What’s in the Middle?

We’ve seen how we can achieve concentration (that’s coordinate-wise sensitive in its bounds) by restricting ourselves to:

- Well-behaved functions and bounded random inputs (Talagrand’s).

- Functions with bounded responses to coordinate change (McDiarmid’s).

Can we get rid of boundedness altogether now, relaxing it to the probibalistic “boundedness” that is subgaussian concentration? Well, yes and no.

How’s this possible?

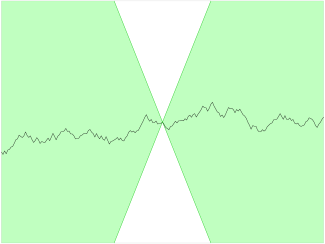

Kontorovich 2014 claims concentration for generic Lipschitz functions for subgaussian inputs. At first, this may sound too good to be true. Indeed, a famous counterexample (BLM Problem 6.4, p. 211, which itself refers to LT p. 25) finds a particular \(f\) where the following holds for sufficiently large \(n\). \[ \P\ca{f(X)> \E f(X)+cn^{1/4}}\ge 1/4\,. \] Technically, the result is shown for the median, not mean value of \(f\), but by integrating the median concentration inequality for Lipschitz functions of subgaussian variables (LT p. 21), we can state the above, since the mean and median are within a constant of each of other (bdd rvs with zero mean are sg). From the proof (LT, p. 25), \(f(X)\) has rate no better than \(t^2n^{-1/2}\).

Therein lies the resolution for the apparent contradiction: we’re pathologically dependent on the dimension factor. On the other hand, the bound proven in the aforementioned Kontorovich 2014 paper is that for sg \(X\), we can achieve a concentration rate \(t^2/\sum_i\Delta_{\text{SG}, i}^2\), where \(\Delta_{\text{SG}, i}\) is a subgaussian diameter, which for our purposes is just a constant times \(\sigma_i^2\), the subgaussian parameter for the \(i\)-th position in the \(n\)-dimensional vector \(X\). For some \(\sigma^2=\max_i\sigma^2\), note that the hidden dimensionality emerges, since the Kontorovich rate is then \(t^2/(n\sigma^2)\).

The Kontorovich paper is a nice generalization of McDiarmid’s inequality which replaces the boundedness condition with a subgaussian one. We still incur the dimensionality penalty, but we don’t care about this if we’re making a one-dimensional or fixed-\(n\) statement. In fact, the rest of the Kontorovich paper investigates scenarios where this dimensionality term is cancelled out by a shrinking \(\sigma^2\sim n^{-1}\) (in the paper, this is observed for some stable learning algorithms).

In fact, there’s even quite a bit of room between the Kontorovich bound \(t^2/n\) (fixing the sg diameter now) and the counterexample lower bound \(t^2/\sqrt{n}\). This next statement might be made out of my own ignorance, but it seems like there’s still a lot of open space to map out in terms of what rates are possible to achieve in the non-convex case, if we care about the dimension \(n\) (which we do).

References

- BLM - Boucheron, Lugosi, Massart (2013), Concentration Inequalities

- LT - Ledoux and Talagrand (1991), Probability in Banach Spaces