Roller Coaster Tycoon 2 (RCT2) Problem

In Roller Coaster Tycoon 2, you play as the owner of an amusement park, building rides to attract guests. One ride you can build is a maze. It turns out that, for visual appeal, guests traverse mazes using a stochastic algorithm.

Marcel Vos made an entertaining video describing the algorithm, which has in turn spawned an HN thread and Math SE post.

I really enjoyed solving the problem and wanted to share the answer as well as some further thoughts.

Mazes in RCT2

A maze in this game is a 2 dimensional grid of tiles, with an entrance tile and an exit tile. The goal for guests is to get to the exit. Hedges on the edges of tiles prevent guests from moving in certain directions, as a result the paths guests can take form a 2-dimensional grid world with only certain movements permitted.

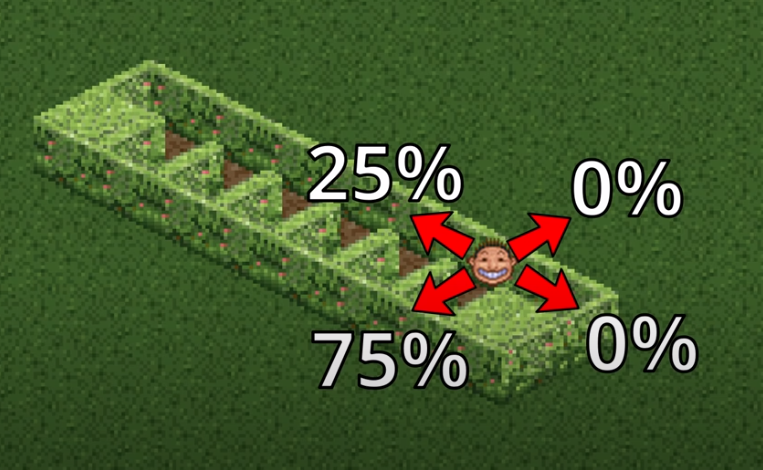

What’s interesting about the maze above, Marcel notices, is that it’s very easy for us to solve if it was a real-world maze, but it takes guests years of in-game time to solve it.

The maze is pretty simple: it’s got one long corridor to the exit (this particular pictured one wraps around, but let’s pretend it just goes straight), and lots of “inlets” to the left that immediately result in dead ends, which no one actually solving the maze would go into.

Movement Dynamics

A closer look at how the guests path find gives some indication of what’s going on.

Marcel does a really great job explaining this, but I’ll give a quick overview.

Whenever a guest enters a tile from a certain direction, the game figures out what “valid” exit tiles would be. In particular,

- any tile blocked by a hedge is invalid and

- the direction of the previous tile the guest came from is invalid, unless it’s the only tile unblocked by a hedge.

Then, the game picks one of the four directions randomly with equal probability. While the chosen direction is invalid, the new chosen direction becomes the direction immediately clockwise to the original one.

In particular, we see that when the guest enters the second tile from the first, as pictured above, they’re facing forward, so moving back is invalid. The right side is blocked. Both right and back directions result in going left by the clockwise bias rule, so there’s a \(75\%\) chance of moving left as pictured.

If you look further into the video, you’ll notice that when you face the other direction, you’re much more likely to move back in the direction of the entrance than going into the inlet.

The RCT2 Problem

Given a maze with a single corridor of length \(n\) with single-tile inlets to the left (facing the exit from from the enterance), how long will it take, on average, for a guest to complete the maze?

A Finite Markov Chain

The Math SE poster took a look at some specific finite values of \(n\) to get a sense of what the solution looks like, and in doing so constructed some valuable abstractions for the problem.

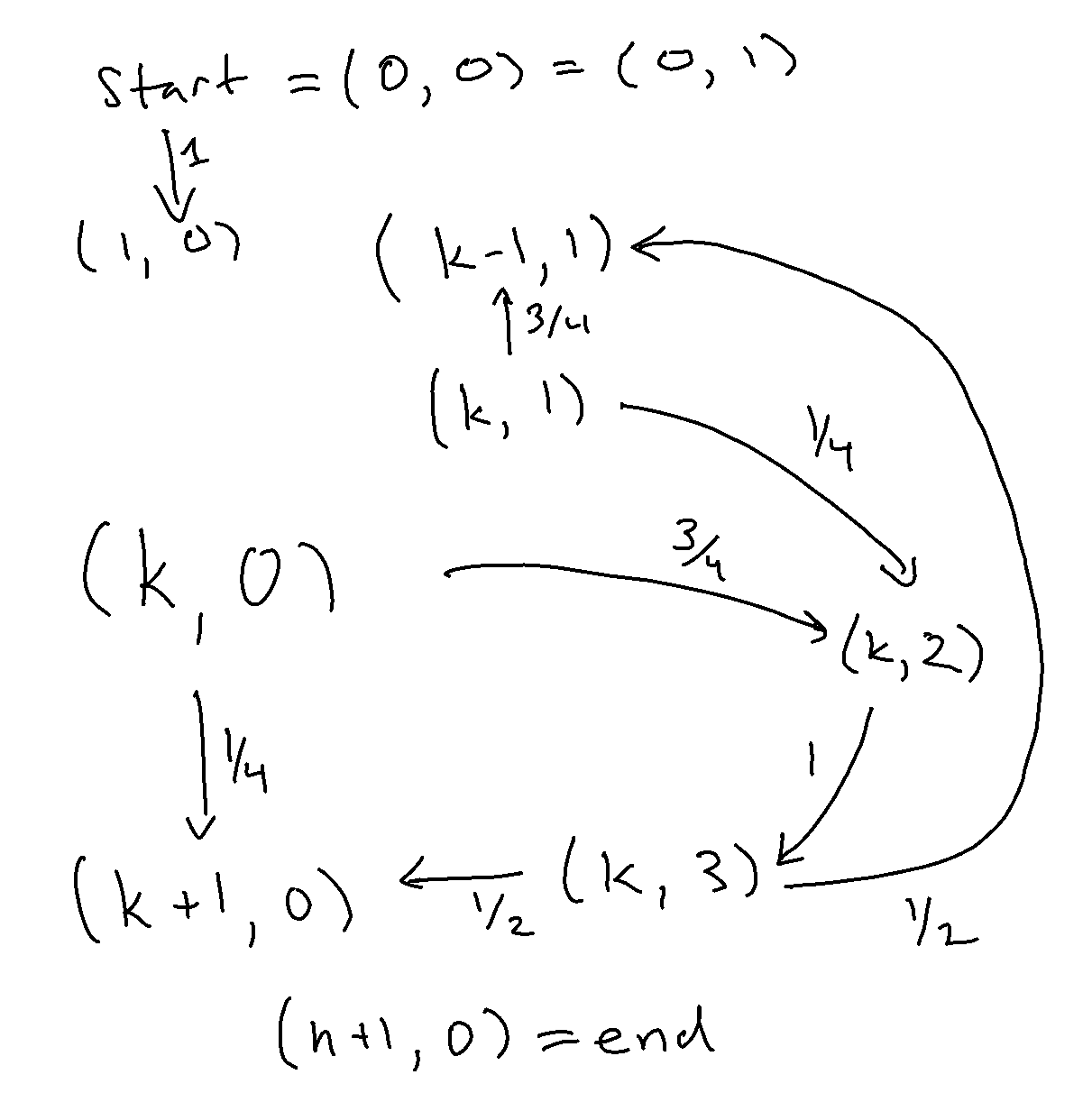

First, let’s describe every state in the maze explicitly. We have \(\mathrm{start},\mathrm{end}\) tiles on either side of the maze.

But between those we have a repeated pattern: you’re either on the \(k\)-th tile of the corridor, where you could be facing forward (towards the exit) or backwards (towards the entrance) or away from the inlet (towards the right hedge, if you came from an inlet), or you’re in an inlet, facing into a hedge.

Computing the probability of the transitions explicitly, we get the following probabilities of transitions:

\[

\begin{align}

P(\mathrm{start} &\to (1,0)) &=& &1\\\

P((k,0) &\to (k+1,0)) &=& &1/4 \\\

P((k,0) &\to (k,2)) &=& &3/4 \\\

P((k,1) &\to (k-1,1)) &=& &3/4 \\\

P((k,1) &\to (k,2)) &=& &1/4 \\\

P((k,2) &\to (k,3)) &=& &1 \\\

P((k,3) &\to (k+1,0)) &=& &1/2 \\\

P((k,3) &\to (k-1,1)) &=& &1/2 \\\

&(n+1, 0)&=& &\mathrm{end}

\end{align}

\]

where the meaning of each state is given by

- \((k, 0)\) - \(k\)-th tile of the corridor, facing forwards

- \((k, 1)\) - \(k\)-th tile of the corridor, facing backwards

- \((k, 2)\) - \(k\)-th tile of the corridor, in the inlet

- \((k, 3)\) - \(k\)-th tile of the corridor, facing the hedge

for all \(k\in[n]\).

This fully defines a Markov chain on \(4n+2\) states. Represented pictorially, each \(k\)-th block looks like the following.

A Finite Approach

The SE poster goes on, providing a solution for specific \(n\).

Let \(P_n\) be the \(4n+1\times 4n+1\) transition matrix of all non-exit states. Then, by matrix multiplication, the \(ij\)-th entry of \(P_n^t\) for \(P_n^t\) for \(t\in\mathbb{N}\) is then the probability that you’re in the \(j\)-th location if you started at the \(i\)-th one and that you have not reached the exit yet by transition matrix multiplication (the exit state is absorbing, you never leave). Then, \(\sum_{t=0}^T P_n^t=(I-P_n)^{-1}\) contains the expected number of visits to the \(j\)-th state within \(T\) steps if starting at state \(i\), as it’s the sum of the probability of a visit at each step \(t\) from \(0\) to \(T\). That means the sum of entries of the first row of \((I-P_n)^{-1}=\sum_{t=0}^\infty P^t\) is the expected number of visits to all non-absorbing states on a walk starting at the first state, i.e., the expected absorption time (because the sum of the probability that you’re in the \(j\)-th state at the \(t\)-th time step across \(t\) gives the total time spent at that state, and the sum of average time spent at all non-exit states is exactly average time spent in the maze)!

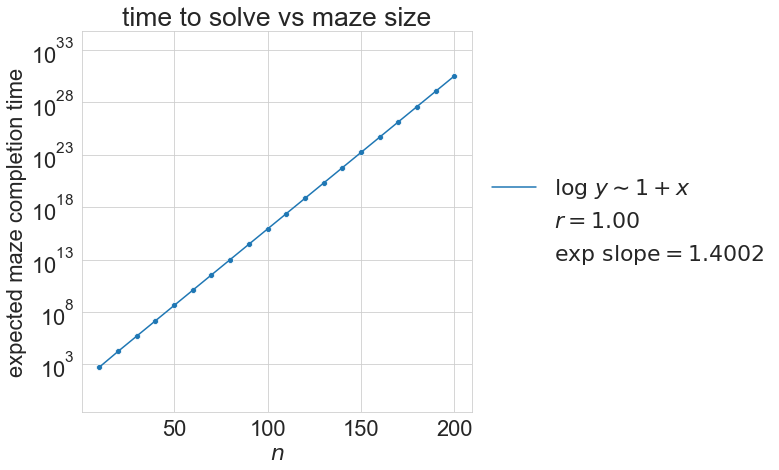

But this means we can literally compute the answer for a specific \(n\) by building \(P_n\) and printing \(\delta_1^\top (I-P)^{-1}\mathbf{1}\). That’s just what our poster did.

Sure enough, our time to solve clearly follows an exponential pattern.

But, how do we prove this? Tune in next time for the RCT2 Solution.