BERT Prerequisite 2: The Transformer

In the last post, we took a look at deep learning from a very high level (Part 1). Here, we’ll cover the second and final prerequisite for setting the stage for discussion about BERT, the Transformer.

The Transformer is a novel sequence-to-sequence architecture proposed in Google’s Attention is All You Need paper. BERT builds on this significantly, so we’ll discuss here why this architecture was important.

The Challenge

Recall the language of the previous post applied to supervised learning. We’re interested in a broad class of settings where the input \(\textbf{x}\) has some shared structure with the output \(\textbf{y}\), which we don’t know ahead of time. For instance, \(\textbf{x}\) might be an English sentence and \(\textbf{y}\) might be a German sentence with the same context.

For a parameterized model \(M(\theta)\) which might just be a function over \(\textbf{x}\), we recall the \(L\)-layer MLP from last time, where \(\theta=\mat{\theta_1& \theta_2&\cdots&\theta_L}\), \[ M(\theta)= x\mapsto f_{\theta_L}^{(L)}\circ f_{\theta_{L-1}}^{(L-1)}\circ\cdots\circ f_{\theta_1}^{(1)}(x)\,, \] and we define each layer as \[ f_{\theta_i}=\max(0, W_ix+b_i)\,,\,\,\, \mat{W_i & b_i} = \theta_i\,. \]

Most feed-forward neural nets (FFNNs) are just variants on this architecture, with some loss typically like \(\norm{M(\theta)(\textbf{x}) - \textbf{y}}^2\).

One issue with this, and typical FFNNs, is that they’re mappings from some fixed size vector space \(\mathbb{R}^m\) to another \(\mathbb{R}^k\). When your inputs are variable-length sequences like sentences, this doesn’t make sense for two reasons:

- Sentences can be longer than the width of your input space (not a fundamental issue, you could just make \(m\) really large).

- The inputs don’t respect the semantics of the input dimensions.

For typical learning tasks, the \(i\)-th input dimension corresponds to a meaningful position in the input space. E.g., for images, this is the \(i\)-th pixel in the space of fixed size \(64\times 64\) images. It’s next to the \((i-1)\)-th and \((i+1)\)-th pixels, and every \(64\times 64\) image \(\textbf{x}\) will also have its \(i\)-th pixel in the \(i\)-th place.

Not so for sentences. In sentences, the subject may the first or second or third word. It might be preceded by an article, or it might not. If you look at a fixed offset for many different sentences, you’d be hard pressed to find a robust semantics for the word or letter that you see there. So it’s unreasonable to assume a model could extract relevant structure with such a representation.

Recursive Neural Networks (RNNs)

The typical resolution to this problem in deep learning is to use RNNs. For an overview, see Karpathy’s blog post.

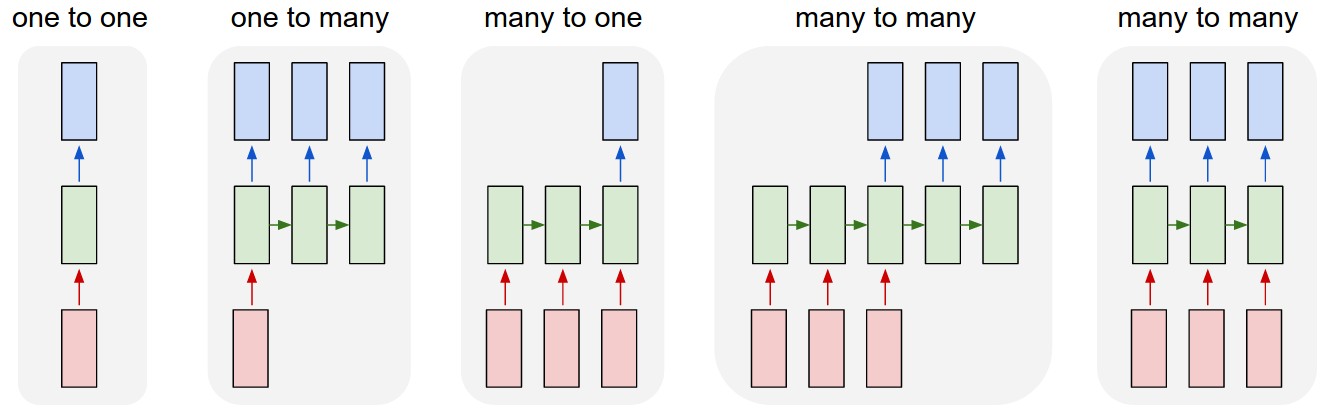

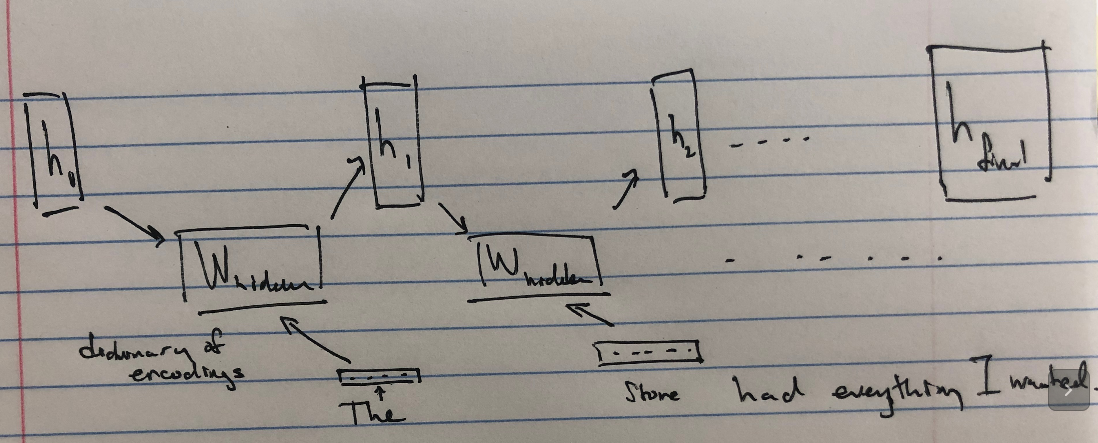

To resolve this issue, we can view our input as a variable-length list of fixed length vectors \(\{\textbf{x}_i\}_{i}\). Next, we modify our FFNN to accept two fixed-length parameters at a time step \(i\), a hidden state \(\textbf{h}_i\) and input \(\textbf{x}_i\). It’s the green box in the diagram above.

This retains essential properties of FFNNs that allow it to optimize well (backprop still works). But, from a perspective of input semantics, we’ve resolved our problem by assuming the hidden state at timestep \(\textbf{h}_i\) tells the FFNN how to interpret the \(i\)-th sequence element (which could be a word or word part or character in the sentence). The FFNN is then also responsible for updating how the \((i+1)\)-th sequence element is to be interpreted, by returning \(\textbf{h}_{i+1}\) on the evaluation in timestep \(i\).

We might want to wait until the network reads the entire input if the entire variable-length output may change depending on all parts of the input (the second to last diagram above). This is the case in translation, where words at the end of the source language may end up at the beginning in the target language.

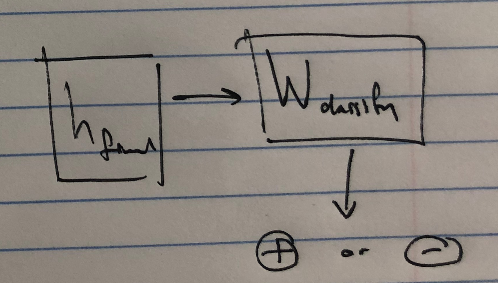

Alternatively, we might do something like try to classify off of the hidden state after reading the sentence, like identifying the sentiment of a text-based review.

RNN challenges

Consider the task of translating English to Spanish. Let’s suppose our inputs are sequences of words, like

I arrived at the bank after crossing the {river,road}.

The proper translation might be either:

Llegué a la orilla después de cruzar el río.

or:

Llegué al banco después de cruzar la calle.

Notice how we need to look at the whole sentence to translate it correctly. The choice of “river” or “road” affects the translation of “bank”.

This means that the RNN needs to store information about the entire sentence when translating. For longer sentences, we’d definitely need to use a larger hidden state, but also we’re assuming the network would even be able to train to a parameter setting that properly recalls whole-sentence information.

The Transformer

The problem we faced above is one of context: to translate “bank” properly we need the full context of the sentence. This is what the Transformer architecture addresses. It inspects each word in the context of others.

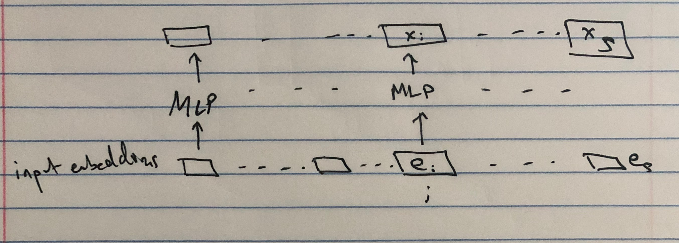

Again, let’s view each word in our input sequence as some embedded vector \(\textbf{e}_i\) (for context on word embeddings, check out the Wikipedia page).

Our goal is to come up with a new embedding for each word, \(\textbf{a}_i\), which contains context from all other words. This is done through a mechanism called attention. For a code-level explanation, see The Annotated Transformer, though I find that focusing on a particular word (the one at position \(i\)) helped me understand better.

The following defines (one head of) a Transformer block. A transformer block just contextualizes embeddings. They can be stacked on top of each other and then handed off to the transformer decoder, which is a more complicated kind of transformer that includes attention over both the inputs and outputs. Luckily, we don’t need that for BERT.

Remember, at the end of the day, we’re trying to take one sequence \(\{\textbf{e}_i\}_i\) and convert it into another sequence \(\{\textbf{a}_i\}_i\) which is then used as input for another stage that does the actual transformation. The point is that the representation \(\{\textbf{a}_i\}_i\) is broadly useful for many different decoding tasks.

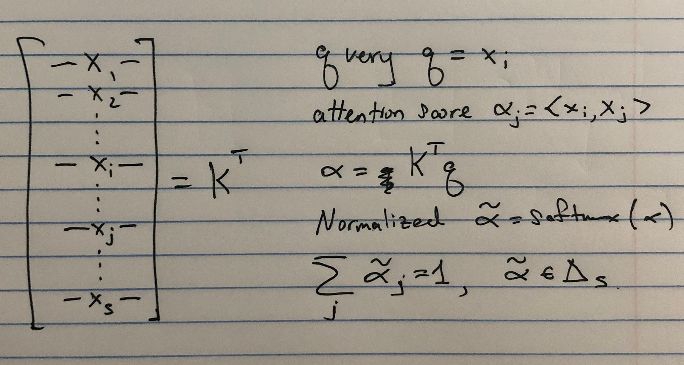

- Apply an FFNN pointwise to each of the inputs \(\{\textbf{e}_i\}_i\) to get \(\{\textbf{x}_i\}_i\).

- Now consider a fixed index \(i\). How do we contextualize the word at \(\textbf{x}_i\) in the presence of other words \(\textbf{x}_1,\cdots,\textbf{x}_{i-1},\textbf{x}_{i+1},\cdots,\textbf{x}_s\)?

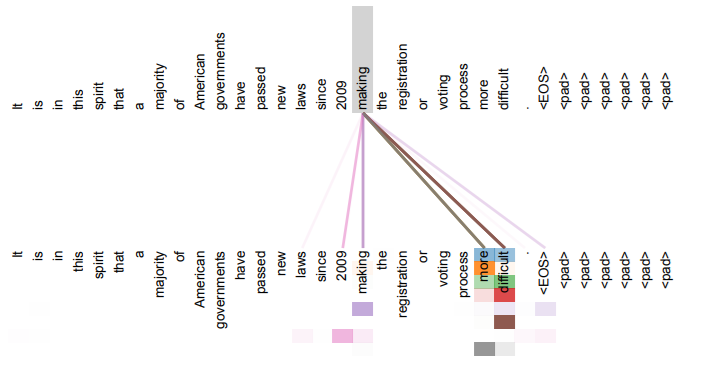

We attend to the sequence itself. Attention tells us how much to pay attention to each element when coming up with a fixed-width context for the \(i\)-th element. This is done with the inner product.

After computing how important each element \(\textbf{x}_j\) is to the element in question \(\textbf{x}_i\) as \(\alpha_j\), we combine the weighted sum of each of the \(\textbf{x}_j\) themselves.

- After doing this for every index \(i\in[s]\), we get a new sequence \(\textbf{a}_i\). That’s it!

This glosses over a couple normalization, multiple heads, and computational details, but it’s the gist of self-attention and the Transformer block.

One thing worth mentioning is the positional encoding, which makes sure that information about a word being present in the \(i\)-th position is present before the first Transformer block is applied.

After possibly many transformer blocks, we get our \(L\)-th sequence of embeddings, \(\{\textbf{a}^{(L)}_i\}_i\). We plug this as input to another model, the transformer decoder, which uses a similar process to eventually get a loss based on some input-output pair of sentences (e.g., in translation, the decoder converts the previous sequence into \(\{\textbf{b}_j\}_j\), which is compared with the actual translation \(\{\textbf{y}^{(L)}_j\}_j\)

So What?

On the face of it, this all sounds like a bunch of hand-wavy deep learning nonsense. “Attention”, “embedding”, etc. all look like fancy words to apply to math that is operating on meaningless vectors of floating-point numbers. Layer on top of this (lol) the other crap I didn’t cover, like multiple heads, normalization, and various knobs pulled during training, and the whole thing looks suspect.

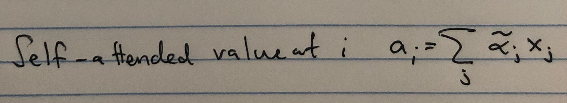

It’s not clear which parts are essential, but something is doing its job:

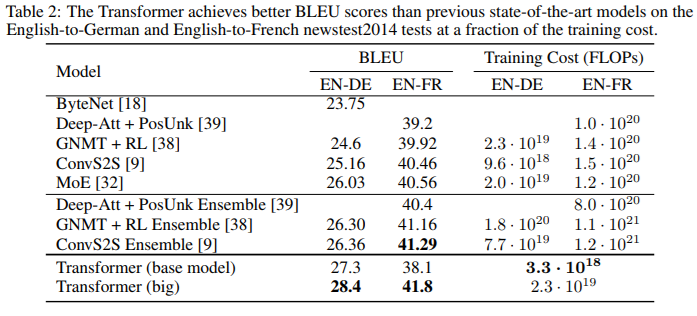

And self-attention looks like it’s doing something like what we think it should.

Regardless how much of a deep learning believer you are, this architecture solves problems which require contextualizing our representation of words, and it picks the right things to attend to in examples.

Next time

We’ll see how BERT uses the context-aware Transformer to come up with a representation without any supervision.